Welcome this

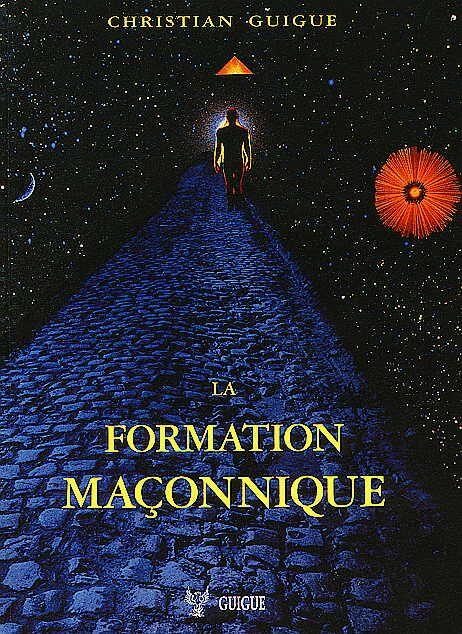

Christian Guigue

french masonic

site of Research

This Christian Guigue french site

is

designated

AWARD OF EXCELLENCE

Reading Masons

and

Masons who do not Read

By Albert G. Mackey

(published in 1875 by The Master Mason

- October 1924)

I suppose there are more Masons who are ignorant of all the

principles of Freemasonry than there are men of any other class who are chargeable with

the like ignorance of their own profession, There is not a watchmaker who does not

know something about the elements of horology, nor is there a blacksmith who is altogether

unacquainted with the properties of red-hot iron. Ascending to the higher walks of

science, we would be much astonished to meet with a lawyer who was ignorant of the

elements of jurisprudence, or a physician who had never read a treatise on pathology, or a

clergyman who knew nothing whatever of theology. Nevertheless, nothing is more common than

to

encounter Freemasons who are in utter darkness as to every thing that relates to

Freemasonry. They are ignorant of its history - they know not whether it is a mushroom

production of today, or whether it goes back to remote ages for its origin. They have no

comprehension of the esoteric meaning of its symbols or its ceremonies, and are hardly at

home in its modes of recognition. And yet nothing is more common than to find such

sciolists in the possession of high degrees and sometimes honored with elevated affairs in

the Order, present at the meetings of lodges and chapters, intermeddling with the

proceedings, taking an active part in all discussions and pertinaciously maintaining

heterodox opinions in opposition to the judgment of brethren of far greater knowledge.

Why, it may well be asked, should such things be ? Why, in Masonry alone, should there be

so much ignorance and so much presumption ? If I ask a cobbler to make me a pair of boots,

he tells me that he only mends and patches, and that he has not Iearned the higher

branches of his craft, and then hie honestly declines the offered job. If I request a

watchmaker to construct a mainspriiig for my chronometer, he answers that he cannot do it,

that he has never learned how to make mainsprings, which belongs to a higher branch of the

business, but that if I will bring him a spring ready made, he will insert it in my

timepiece, because that he knows how to do. If I go to an artist with an order to paint me

an historical picture, he will tell me that it is beyond his capacity, that he has never

studied nor practiced the comportion of details, but has

confined himself to the painting of portraits. Were he dishonest and presumptuous he would

take my order and instead of a picture give me a daub.

It is the Freemason alone who wants this modesty. He is too apt to think that the obligation not only makes him a Mason, but a learned Mason at the same time. He too often imagines that the mystical ceremonies which induct him into the Order are all that are necessary to make him cognizant of its principles. There are some Christian sects who believe that the water of baptism at once washes away all sin, past and prospective. So there are some Masons who think that the mere act of initiation is at once followed by an influx of all Masonic knowledge. They need no further study or research. All that they require to know has already been received by a sort of intuitive process.

The great body of Masons may be divided into three

classes. The first consists of those who made their application for initiation not from a

desire for knowledge, but from some accidental motive, not always honorable. Such men have

been led to seek reception either because it was likely, in their opinion, to facilitate

their business operations, or to advance their political prospects, or in some other way

to personally benefit them. In the commencement of a war, hundreds flock to the lodges in

the hope of obtaining the "mystic sign," which will be of service in the hour of

danger. Their object having been attained, or having failed to attain it, these men become

indifferent and, in time, fall into the rank of the non-affiliates. Of such Masons there

is no hope. They are dead trees

having no promise of fruit. Let them pass as utterly worthless, and incapable of

improvement.

There is a second class consisting of men who are the moral and Masonic antipodes of the

first. These make their application for admission, being prompted, as the ritual requires,

"by a

favorable opinion conceived of the Institution, and a desire of knowledge." As soon

as they are initiated, they see in the ceremonies through which they have passed, a

philosophical meaning worthy of the trouble of inquiry. They devote themselves to this

inquiry. They obtain Masonic books, they read Masonic periodicals, and they converse with

well-informed brethren. They make themselves acquainted with the history of the

Association. They investigate its origin and its ultimate design. They explore the hidden

sense of its symbols and they acquire the interpretation. Such Masons are always useful

and honorable members of the Order, and very frequently they become its shining lights.

Their lamp burns for the enlightenment of others, and to them the

Institution is indebted for whatever of an elevated position it has attained. For them,

this article is not written.

But between these two classes, just described, there is an intermediate one; not so bad as

the first, but far below the second, which, unfortunately, comprises the body of the

Fraternity.

This thirdclass consists of Masons who joined the Society with unobjectionable motives,

and with, perhaps the best intentions. But they have failed to carry these intentions into

effect.

They have made a grievous mistake. They have supposed that initiation was all that was

requisite to make them Masons, and that any further study was entirely unnecessary. Hence,

they never read a Masonic book. Bring to their notice the productions of the most

celebrated Masonic authors, and their remark is that they have no

time to read-the claims of business are overwhelming. Show them a Masonic journal of

recognized reputation, and ask them to subscribe. Their answer is, that they cannot afford

it, the times are hard and money is scarce.

And yet, there is no want of Masonic ambition in many of these men. But their ambition is

not in the right direction. They have no thirst for knowledge, but they have a very great

thirst for office or for degrees. They cannot afford money or time for the purchase or

perusal of Masonic books, but they have enough of both to expend on the acquisition of

Masonic degrees.

It is astonishing with what avidity some Masons who do not understand the simplest

rudiments of their art, and who have utterly failed to comprehend the scope and meaning of

primary, symbolic Masonry, grasp at the empty honors of the high degrees. The Master Mason

who knows very little, if anything, of the Apprentice's degree longs to be a Knight

Templar. He knows

nothing, and never expects to know anything, of the history of Templarism, or how and why

these old crusaders became incorporated with the Masonic brotherhood. The height of his

ambition is to wear the Templar cross upon his breast. If he has entered the Scottish

Rite, the Lodge of Perfection will not content him, although it supplies material for

months of study. He would fain rise higher in the scale of rank, and if by persevering

efforts he can attain the summit of the Rite and be invested with the Thirty-third degree,

little cares he for any knowledge of the organization of the Rite or the sublime lessons

that it teaches. He has reached

the height of his ambition and is permitted to wear the double-headed eagle.

Suxh Msons are distinguished not by the amount of knowledge that they possess, but by the

number of the jewels that they wear. They will give fifty dollars for a decoration, but

not fifty cents for a book.

These men do great injury to Masonry. They have been called its drones. But they are more

than that. They are the wasps, the deadly enemy of the industrious bees. They set a bad

example to the younger Masons - they discourage the growth of Masonic literature - they

drive intellectual men, who would be willing to cultivate Masonic science, into other

fields of labor - they depress the energies of our writers - and they debase the character

of Speculative Masonry as a branch of mental and moral philosophy. When outsiders see men

holding high rank and office in the Order who are almost as ignorant as themselves of the

principles of Freemasonry, and who, if asked, would say they looked upon it only as a

social institution, these outsiders very naturally conclude that there cannot be anything

of great value in a system whose highest positions are held by men who profess to have no

knowledge of its higher development.

It must not be supposed that every Mason is expected to be a learned Mason, or that every

man who is initiated is required to devote himself to the study of Masonic science and

literature. Such an expectation would be foolish and unreasonable. All men are not equally

competent to grasp and retain the same amount of knowledge. Order, says Pope-Order is

heaven's first law and this confest, Some are, and must be, greater than the rest, More

rich, more wise.

All that I contend for is, that when a candidate enters the fold of Masonry he should feel

that there is something in it better than its mere grips and signs, and that he should

endeavor with all his ability to attain some knowledge of that better thing. He should not

seek advancement to higher degrees until he knew something of the lower, nor grasp at

office, unless he had previously fulfilled with some reputation for Masonic knowledge, the

duties of a private station. I once knew a brother whose greed for office led him to pass

through all the grades from Warden of his lodge to Grand Master of the jurisdiction, and

who during that whole period had never read a Masonic book nor attempted to comprehend the

meaning of a single symbol. For the year of his Mastership he always found it convenient

to have an excuse for absence from the lodge on the nights when degrees were to be

conferred. Yet, by his personal and social influences, he had succeeded in elevating

himself in rank above all those who were above him in Masonic knowledge. They were really

far above him, for they all knew something, and he knew nothing. Had he remained in the

background, none could have complained. But, being where he was, and seeking himself the

position, he had no right to be ignorant. It was his presumption that constituted his

offense.

A more striking example is the following: A few

years ago while editing a Masonic periodical, I received a letter from the Grand Lecturer

of a certain Grand Lodge who had been a subscriber, but who desired to discontinue his

subscription. In assigning his reason, he said (a copy of the letter is now before me),

"although the work contains much valuable information, I shall have no time to read,

as I shall devote the whole of the present year to teaching." I cannot but imagine

what a teacher such a man must have been, and what pupils he must have instructed.

This article is longer than I intended it to be. But I feel the importance of the subject.

There are in the United States more than four hundred thousand affiliated Masons. How many

of these are readers ? One-half - or even one-tenth ? If only one-fourth of the men who

are in the Order would read a little about it, and not depend for all they know of it on

their visits to their lodges, they would entertain more elevated notions of its character.

Through their sympathy scholars would be encouraged to discuss its principles and to give

to the public the results of their thoughts, and good Masonic magazines would enjoy a

prosperous existence.

Now, because there are so few Masons that read, Masonic books hardly do more than pay the

publishers the expense of printing, while the authors get nothing; and Masonic journals

are

being year after year carried off into the literary Acaldama, where the corpses of defunct

periodicals are deposited; and, worst of all, Masonry endures depressing blows.

The Mason who reads, however little, be it only the pages of the monthly magazine to which

he subscribes, will entertain higher views of the Institution and enjoy new delights in

the possession of these views. The Masons who do not read will know nothing of the

interior beauties of Speculative Masonry, but will be content to suppose it to be

something like Odd Fellowship, or the Order of the Knights of Pythias - only, perhaps, a

little older. Such a Mason must be an indifferent one. He has laid no foundation for zeal.

If this indifference, instead of being checked, becomes more widely spread, the result is

too apparent. Freemasonry must step down from the elevated position which she has been

struggling,

through the efforts of her scholars, to maintain, and our lodges, instead of becoming

resorts for speculative and philosophical thought, will deteriorate into social clubs or

mere benefit societies. With so many rivals in that field, her struggle for a prosperous

life will be a hard one.

The ultimate success of Masonry depends on the intelligence of her disciples

![]()

.